This one is entirely personal.

Banks’s Culture series is famous, for good and for ill, for its vision of what a galactic-scale post-scarcity society might actually look like. Whatever. I like Consider Phlebas for a more primal reason: Big Thing Go Smash. It’s a picaresque that consists primarily of increasingly over-the-top set-piece action sequences, each one more of a clusterfuck than the last. Somehow it manages to be both a white-knuckle thrill ride from start to finish and also an understated, slowly unfolding tragedy.

Outer Wilds (not to be confused with The Outer Worlds) is a game about space archaeology: exploring a solar system to understand who was there before you and what happened to them. It features realistic physics (you will learn some hard truths about orbital dynamics, whether you thought you wanted to or not), cozy camping-themed art design, a memorably effective score, and puzzle design that is gated only by your own steadily growing knowledge of how the game universe works. As you play, it subtly evolves from the game you think it’s going to be into a different one, and the emotional tenor becomes quietly devastating—while never losing sight of the joy and curiosity that sets the game in motion.

Carissa’s Wierd is the best band you’ve never heard of. They were active from 1999 to 2003, and their quiet, introspective indie rock (with violin) had surprisingly deep influence on the Seattle music scene. Many of their songs are excellent, but I think this one best captures what made them special.

Manifold Garden is a first-person puzzler; its central mechanic is that you can change the direction of gravity to any of the six principal three-dimensional directions. The puzzles are good, but the spaces that define those puzzles are astonishing. Chyr describes himself as an “artist,” and Manifold Garden’s sensibility is fundamentally architectural. Everything is austere, mysterious, and haunting, and the ability to move through and reorient these unsettling spaces is absolutely essential to the experience.

Piranesi is a slim, elegant novel, but it has the same eye and ear for the uncanny as Clarke’s sprawling and discursive Jonathan Strange & Mr Norrell. Presenting vast and ruined spaces through the eyes of a character utterly unaware how strange and unsettling they are is a masterstroke. It can be tough to bring backrooms-adjacent fiction to a satisfying conclusion, but Clarke absolutely sticks the landing. To say more would be to spoil the delights of this strange but utterly assured novel.

An astonishingly creative book about a brilliantly erudite single mother sinking into profound depression and her even more brilliant 11-year-old son’s quest to find a suitable substitute father—and a book that could only have been written by a brilliantly erudite author sinking into profound depression. DeWitt is unmatched at using repetition for comedic (and tragic) effect, and her decision to avoid quotation marks is gives the book a unique rhythm. The first great novel of the 21st century.

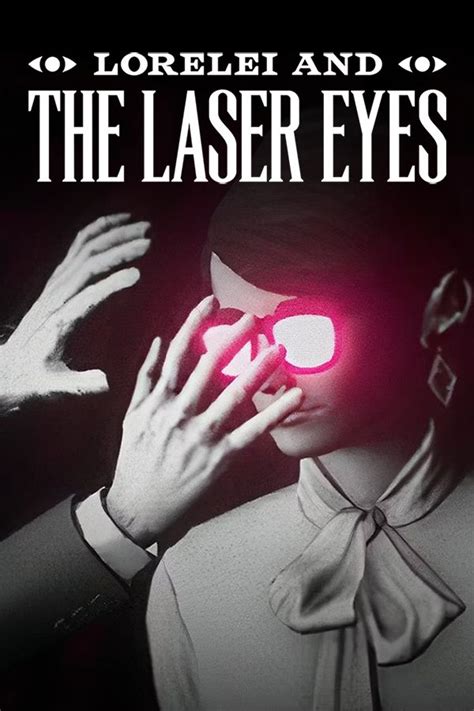

An artist arrives at a mysterious and deserted hotel to collaborate with an eccentric filmmaker, and reality runs off the rails almost immediately. The game itself is a third-person puzzle hunt, as you gradually unlock new areas while exploring the hotel and what might be illusions, art projects, or the disintegration of the world itself. Rendered in stark black-and-white with flashes of vivid red and magenta, Lorelei and the Laser Eyes seems like it might just be all style … except that its many, many flights of fancy come together in a conclusion that feels not just satisfying but almost inevitable. Enjoy the ride, and a thoughtful meditation on art and madness.

Yes, another space archaeology game. This one’s top-line pitch is that you decipher an ancient language, while piecing together the history of a “Nebula” where people sail on space rivers from moon to moon. Although the game is contemplatively paced and primarily dialogue-driven, it instills an exceptional sense of rising dread: these long-abandoned places are full of memories and ghosts. Laurence Chapman’s score for piano and string quartet is so perfect that I bought the study score and have been reveling in it for years.

Lem’s science fiction is filled with failures of communication, as humans encounter a universe filled with things beyond their ability to comprehend. The Pirx stories, spread across two volumes in English, leaven this bleakness with action and irony. Pirx is a pragmatic Everyman; he is clever enough to know that trying to be clever will only get you killed. Every story is a gem, but “Terminus” and “Pirx’s Tale” are all-time classics. Bonus: The Invincible takes enormous liberties with the Lem novel it is based on, but manages to capture its spirit.

In another place or at another time, I might have picked Italo Calvino’s Invisible Cities or Alan Lightman’s Einstein’s Dreams as my recommendation in the micro-genre of dream-variations on a theme at the border of reality and myth. But here and now there is something about the emotional arc of The Lost Books of the Odyssey that makes it stand out for me. Ask me again elsewhere and elsewhen, and perhaps my answer will always have been different.

This cover of a song by Katell Keineg is on Merchant’s 1999 live album and DVD. It’s a ballad of love and unbridgable loss, a slow and mournful counting rhyme that gradually builds to an emotionally wrenching climax. I made a mixtape once that I used for comfort in difficult times; Gulf of Araby was the closing track on Side A, the last step in taking myself apart emotionally before Side B started the work of putting things back together.

The first real piece of fine art I bought was from this series. Some things just speak to you.

Velázquez’s 1656 Las Meninas, a portrait of the five-year-old infanta Margaret Theresa and her entourage, is part of the European canon. Almost exactly four centuries later, Picasso painted a series of fifty-eight deconstructions of the Velázquez original. Per his wishes, they are kept together in the collection of the Museu Picasso in Barcelona, where they are usually displayed as a group. Individually, they are mid, but seeing them all together is a stunning experience, like watching a hypercube (or is that hyper-cubism?) unfold. It changed the way I experience art.

I have given away more copies of The Gold Bug Variations than of any other book. It could also easily have been on my list of intricate works of fiction, but that’s Richard Powers for you: brains and heart.

The “humming chorus” is a brief, wordless bridge from Act II to Act III of Madame Butterly, a moment of transcendent grace and calm before the hammer blows that lie ahead for Cio-Cio-San.

Is Gorogoa the best video game ever made? Yes, Gorogoa is the best video game ever made. Its core mechanic is simplicity itself: slide four pictures around to the quadrants of a 2x2 grid. When the scenes align, people and objects move, opening up new visual options. The puzzles are clever and varied, but the art steals the show. Hand-drawn and symbolically rich, it makes the game into a playable version of the Voynich manuscript or Codex Seraphinianus: a moving journey through a haunting dream-world. The fourth act, in particular, is a wordless story of loss and healing that weaves together picture frames, shattered dishes, and pilgrims’ treks into an unforgettable experience. Don’t miss Roberts’s GDC talk unpacking his thoughtful design decisions.

Passage is a brief game about life. Play it once, and only once.

Blue Prince is superficially a roguelite first-person puzzler about placing rooms on a mansion’s floorplan, but it gradually unfurls into a puzzlehunt wrapped around a family story, both of which go unbelievably deep. Ros has said that his goal was to defy players’ expectations—and then surpass them. Every detail speaks to the care with which this game was made, right down to the gentle, punnish sense of humor. Delight after delight.

Roy does things with language, astonishing things that I will never begin to comprehend.

This comedy narrative game is based on the papers of Elizbethan physician Simon Forman. You have to diagnose and treat patients (“querents”) with a mixture of astrology, humorism, and psychological manipulation. Everything about the game is joyfully silly, from the querents’ absurd concerns to the pop-up-book art style. Special mention for Andrea Boccdoro and Katharine Neil’s score, which gives each character their own Renaissance madrigal:.

At first, it’s a Doom map of a suburban house. Then you start to notice that something’s wrong with the level geometry, and soon you are exploring bizarre liminal spaces inspired by found-footage horror and Mark Z. Danielewski’s House of Leaves (itself a remarkable trip). What could have been a one-joke conceit instead becomes something vast and haunting. Jack Nicholls’s video essay about it is an essential guide, and a work of art in its own right.

This tomb-like cast-concrete monument to the Jewish “people of the book” murdered in the Holocaust is lined with books turned inward so they cannot be read. Its doors have no handles and cannot be opened.